Ei samling restar

Jorunn Veiteberg

Ei samling restar-ein serie om strikk.

Published in the book: Archive; The Unfinished Ones, Magikon forlag, 2011

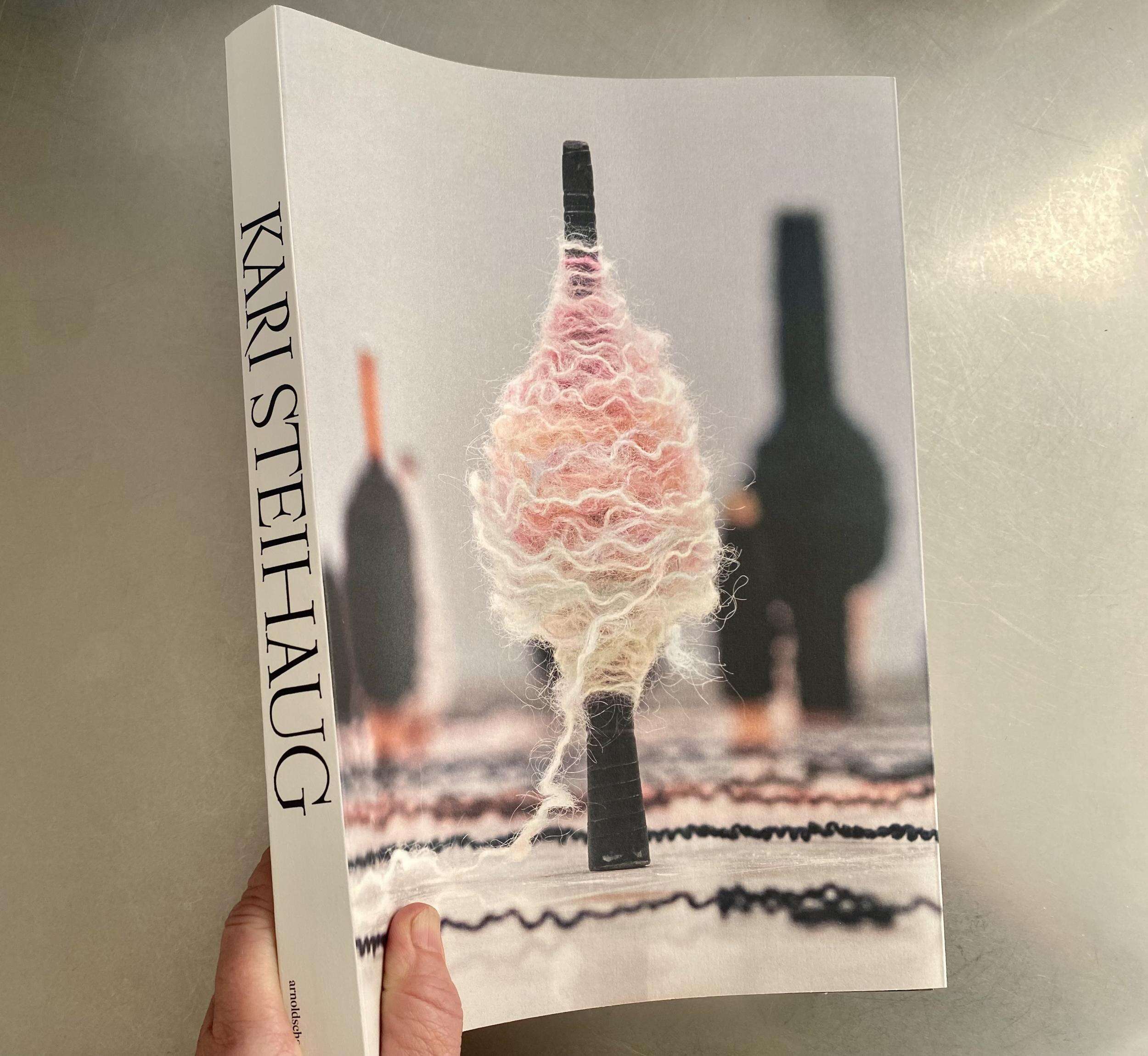

Ein ruin, ikkje av steinar, men av strikk: Stablar av plagg lagt tett i tett slik at dei dannar ein mur. Det var synet som møtte dei besøkande på Kari Steihaug si separatutstilling på Vestlandske Kunstindustrimuseum i 2007, ei utstilling som innleia temaåret deira om strikk. Ruinhadde ho sett som tittel på installasjonen, og den mjuke muren såg ut til å kunna rasa saman når som helst. Om han var meint å vera ein skulptur eller ein fillehaug, eitbyggverk eller ein ruin, eit monument eller eit anti-monument, er ikkje godt å seia. Like ustabilt som verket var reint fysisk, like rørleg er tydinga. Dette er karakteristisk for ruinen, og kan forklara kvifor kunstnarar i fleire hundre år har blitt dregne mot dette motivet.1Fragmentert som ruinen er, står den fram som både open og sårbar. Samstundes uttrykkjer han forandring: i går var han noko anna enn det han er i dag, og den prosessen vil halda fram. Det at ingenting er fast, men er i ei stadig omforming, er typisk for det moderne livet. Filosofen Walter Benjamin framhevar difor ruinen som eit framifrå allegorisk emblem, og som Craig Owens har peika på, heng dette saman med at eit karakteristisk trekk ved allegorien er eit ønske om å trekkja fortidamed seg i notida.2Lest som ein allegori, rommar ruinmotivet ei spenning: Her finst både ein impuls til å samla inn og ta vare på, og ei dragning mot krafta som finst i det fragmentariske og uperfekte. Dette perspektivet gir meining i møte med Ruin. Over 800 handstrikka plagg utgjer byggesteinane i dette verket. Kven som har strikka dei, er ikkje kjent. Kunstnaren har kjøpt plagga på loppemarknader, som ein redningsaksjon. Men ein gong har nokon lagt ned tid og arbeid i å strikka desse kleda; og ein gong har nokon brukt dei av praktiske eller andre grunnar. No er deira tid ute, i alle fall fyller ikkje desse plagga lenger nokon funksjon for eigaren.Ved å byggja ein ruin av dette materialet, har Kari Steihaug skapt ei allegorisk forteljing om ein handarbeidskultur i endring. Delane som har rasa ut, kan tyda på at forfall og oppløysing truar, og mørke fargetonar er med til å underbyggja ei slik dyster tolking. Men samstundes gir fargebruken ruinen tyngde. Han strekkjer seg ut i rommet og skapar ei tydeleg grense som kan tena både som hindring og vern. Opptrekte trådar ligg som eit spindelvevsnett over det heile. Dei kan like gjerne markera byrjinga til noko nytt som avsluttinga på noko gamalt. Ein kultur i endring kan handla om det som har forsvunne og gått tapt, eller det som lever vidare i nye former. Når det gjeld strikking, er det såleis stadig fleire som hevdar at det er i ferd med å skje ei oppbløming.3I så måte plasserer Ruinseg som eit fleirtydig verk i spennet mellom det forgjengelege og varige, detsom var og det som skal bli, slit og lyst, sorg og glede. Det er tema som går som raude trådar gjennom Kari Steihaug sin kunstnarlege produksjon. OpphopingMengda talar sitt eige språk i Ruin. Vi ser ikkje dei einskilde plagga, for dei er filtra saman og stabla i haugar. Ei slik samling av ting, som ikkje er ordna etter deira bruksfunksjon, men dannar ei opphoping, er utbreidd i dagens skulptur eller installasjonskunst. Kunsthistorikaren Lise Skytte Jakobsen framhevar at det som skjer ved bruk av dette organiseringsprinsippet, er ei dekontekstualisering av tinga: ”Tingene bliver simpelthen til noget andet ved at blive organiseret på denne måde. Ophobningen truer med andre ord objekternes selvberoende identitet og deres stabile betydning.”4Vi erfarar også denne typen skulpturar annleis enn den klassiske, slutta skulpturen. Dels krev den at vi går og står på nye måtar alt etter kor omfangsrik installasjonen er, og dels oppmodar den ikkje til berøring i form av klapp og stryk. I staden brukar ein i møtet med opphopinga fingrane (i tankane) til å pilla, lirka, omplassera og føya til.5At det i det heile kunne oppstå kunst som byggjer på opphoping (og masse, som er eit anna typisk organiseringsprinsipp for kunsten det siste hundreåret), heng saman med danninga av eit nytt postmoderne kunstomgrep. Der den klassiske kunsten byggjer på ei forståing av verket som eineståande og originalt, skapt som det er av ein genial kunstnar, så inneber opphopingar ofte ein direkte eller indirekte kritikk av eit slikt ”auratisk” kunstomgrep. Materiala som dannar opphopinga, er gjerne produserte av ulike personar eller verksemder. Kunstnaren si rolle er å samla, arkivera, arrangera og presentera dei på nye måtar. Det særlege ved Ruiner at byggesteinane ikkje utgjer industrielt framstelte, masseproduserte ting eller kopiar, men mengder av handlaga strikk som ber med seg si eiga folkelege kulturhistorie.Lise Skytte Jakobsen koplar opphopingsprinsippet til tema som samling, minne og historie.6Tre emne som er dekkjande for Kari Steihaug sin kunst, og som alle møtest i det aktuelle prosjektet Arkiv; De ufullendte. I motsetning til i Ruiner opphoping ikkje nytta som organiserande prinsipp. Snarare er dette verket prega av eit anna moderne organiseringsprinsipp, serien. Materialet er strikketøy som kunstnaren har samla. Nærare bestemt handlar det om påbegynte plagg som folk (les: kvinner) har hatt liggjande og av ulike grunnar aldri har fått gjort ferdige. Det er både underhaldande og tankevekkjande å lesa grunnane til at dei har gitt opp. For strikkeforsøka er presenterte saman med ein kort tekst som er basert på opphavskvinnene sine forklaringar, men skrive ned og redigert av kunstnaren. I valet av material og metode insisterer Arkiv; De ufullendtepå autentisitet: Dette er verkelege saker frå det verkelege livet. Strategien kan samanliknast med den vitskaplege tilnærminga musea brukar når dei skal bestemma ein gjenstand sin proveniens og historie. Og dermed blir denne forma for kunstnarleg realisme også ein katalysator for dei involverte sitt eige minnearbeid. Men denne realismen er berre ei side ved dette komplekse verket. Når ein ting blir detaljert skildra, blir den også på forunderleg vis mindre familiær. Ved at den ikkje lenger berre blir tatt for gitt, får den ein aura av nokogåtefullt over seg. Frå å representera noko trivielt, blir strikketøya ved at kunstnaren vel ut, samlar, klassifiserar og ordnar dei i eit system, rett og slett uvanlege.Samling I meir enn ti år har Kari Steihaug samla på uferdige og mislukka plagg. Kjeldematerialet ho har å ausa av, er mykje meir omfattande enn det som førebels er blitt formidla i kunstnarleg form i Arkiv: De ufullendte. På Statens Kunstutstilling (Haustutstillinga) i 2009 viste ho sytti utvalde døme. Alle var fotograferte kvar for seg, men presentert i same storleik og i lik innramming, tett i tett i fire rekkjer. Slik skapte ho eit nytt system for dokumentasjon og formidling av samlinga. Som kunstnar nærmar ho seg samlaren både i måten ho organiserer materialet sitt på, og i interessafor variantar og variasjonar. Men i Arkiv: De ufullendteer rekkjene med eksempel ikkje fullstendige. I den siste har ho late to plassar stå tomme, som ein indikator på at meir materiale kan koma til. Forteljinga om dei uferdige plagga er tilsynelatande ikkje slutt. Som filosofen Jean Baudrillard har vore inne på, er det dette som garanterer serien liv. Å fullenda ein serie er å døy, medan mangelen garanterer liv.7Det er ein velkjent påstand at samlingar seier meir om samlaren enn om den som har laga tinga. Når ting, eller som her fragment av plagg, er tatt ut av sin naturlege samanheng, fungerer dei ikkje lenger som eit bindeledd mellom opphavspersonen og omverda. Definert av ramma som samlinga utgjer, peikar dei i staden tilbake på samlaren.8I Arkiv: De ufullendteer strikkefragmenta å rekna som orda i kunstnaren sitt vokabular, og då spelar det ingen rolle at ho ikkje har strikka dei sjølv. Som med samlingar flest tener også denne fleire formål: opplysing og oppseding er mellom dei mest opplagte,9mensamstundes stadfestar Arkiv: De ufullendtekunstnaren si forankring i ein tekstil tradisjon. Strikk som handarbeid og strikk som kunstkonsept er her ikkje motsetningar, men sameint i eitt og same verk. Samlinga som samling er likevel berre eit underordna tema i dette samansette verket. Meir påtrengjande er spørsmål som har med sjølve materialet å gjera: strikka plagg. Kva er det å strikka? Kvifor strikka? Kven strikkar?StrikkingFolkestrikk eller heimestrikk, kallar kulturhistorikarane vanlege folk sine strikkeplagg. Det er slike produkt Kari Steihaug har samla på. Det er uklart når strikking blei vanleg i Norge, men frå 1700-talet veit vi at strikking var ein del av handarbeidsopplæringa for jenter i fattigskulen, og på 1800-talet var strikking blitt vanleg for kvinner i alle lag av folket. Som Eilert Sundt skriv i 1865: ”Det er vel ingen kvindelig gjerning eller husflids-art, som i den grad er fællesfor det hele kjøn.”10Sidan dess har strikking blitt oppfatta som ein typisk kvinnesyssel, ein lågkulturell, marginalisert amatøraktivitet heilt utan status som kunstnarleg medium før feministiske kunstnarar på 1970-talet begynte å stilla spørsmål ved hierarkiet som rådde rundt valet av material og medium. På utstillinga Kvinnfolkpå Kulturhuset i Stockholm i1975 var Slithögeneit av dei mest minneverdige monumenta: Ein gigantisk haug med strikka sokkar og andre klede som kravde stopping og lapping, prega som dei var av bruk og slitasje. Om ho kan strikka eller ei, veit tilskodaren at det har tatt tid å strikka og stoppa alle desse strømpene, slik det også har tatt tid å slita dei ut. Haugen tente som ei påminning om kvar kvinner sine skapande evner tradisjonelt har blitt kanaliserte. Andre kunstnarar, frå Sheila Hicks til Christian Boltanski, begynte å bruka kledeplagg som metaforar for menneskekroppen. Med det grepet var dei med til å opna for den postmoderne holdninga som er rådande i dag, at alle slags materialar kan vera relevante i kunstnarleg samanheng. Det er på skuldrene til desse pionerane Kari Steihaug står, når ho no samlar inn kvinner sine avbrotne strikketøy og løftar fram historiene som ligg bak. Teknisk vurdert er grunnprinsippet i strikking enkelt, og mest alle kan meistra å leggja opp ei maske. Likevel er det få som er i stand til å avlesa korleis ein genser er laga, kva slags garn som er brukt, korleis mønsteret er konstruert eller kva slags tekniske (strikkefaglege) problem som har blitt løyste undervegs. Sjølv om ikkje Arki: De ufullendtegår i detalj om dette, handlar fleire av forteljingane om slike spørsmål. Myten om at strikking er enkelt, blir punktert, og det er eit aspekt ved Arkiv: De ufullendtesom gjer prosjektet interessant også for kulturforskarar. Som ekspertar på strikking har framheva, er korkje det å læra å strikka eller gleda ved å strikka, særleg godt dokumentert.11Dei utvalde eksempla viser kor mangfaldig strikkekulturen er, og kor mange ulike grunnar det er for å strikka. For dei fleste er strikkinga ein hobby, noko ein driv med for kosen og avkoplinga si skuld. Samstundes er det ofte eit nytteaspekt involvert. Eit nytt skjerf, vottar eller genser, gjerne tiltenkt ein annan person, er planen. Strikking er noko ein gjer for andre og ikkje berre seg sjølv. Mange lærer å strikka medan dei er gravide, for å produsere klede til det komande barnet. Eller plagget skal brukast som gåve til ein kjærast, ektefelle eller barn. Mange draumar og voner er såleis nedfelte i strikketøyet, og forklarar ofte kvifor plagget ikkje blei fullført: Kjærleiken tok slutt før plagget blei ferdig,eller barnet vaks fortare enn strikketøyet. Sorg og sinne avløyste stundom lysta og gleda som i utgangspunktet hadde motivert arbeidet. Sjølv om det aldri blei eit ferdig resultat, er tida som er gått med og kjenslene som er investert, med til å gi arbeidet verdi. I valet av garn og mønster, har kvinnene lagt eit personleg engasjement, sjølv om også skiftande trendar spelar inn. Kombinasjonen av tid, omtanke og kjærleik, kort sagt alle dei gode intensjonane, har rett og slett gjort det vanskeleg å kvitta seg med desse restane. I staden har dei blitt stuva bort til Kari Steihaug fekk tak i dei og gav dei eit nytt liv som kunst. MinneberararDei strikka fragmenta i Arkiv: De ufullendtedemonstrerer det designhistorikaren Judy Attfield har halde fram som karakteristisk for materiell kultur: dei representerer på ei og same tid både noko handgripeleg og noko uhandgripeleg; noko fysisk og materielt så vel som noko sosialt og emosjonelt.12At dei ikkje er blitt kasta, er det tydelegaste provet på at dei rommar noko viktig. Interessant nok gir mange av bidragsytarane uttrykk for stor lette over at Kari Steihaug kan bruka strikketøya deira. Det lyder nærast som ei bør blir tatt frå dei, og at ho med handlinga si frir dei frå banda som tinga representerer. Flyttinga frå den private og heimlege til den offentlege kunstkonteksten, innleier eit nytt kapittel i desse strikketøya sin biografi. I større grad enn før lever dei sitt eige liv, og minna som dei er berarar av, kan bli gjenkjent og verdsett av andre. Vi tolkar klede som uttrykk for personen som har laga eller brukar dei, og for kulturen dei er oppstått i, men plagg kommuniserer meir underforstått og mindre openlyst enn verbalspråket. Som antropologen Grant McCracken minnar om, er det svært avgrensa kva klede kan kommunisera, og med kva retorisk kraft dei kan gjera det.13I endå større grad gjeld det for klede som berre eksisterer som fragment. Styrken, i tydinga evna til å formidla meining, er difor i Arkiv: De ufullendteknytt til mengda og den serielle organiseringa som skapar ein samanheng og ei tolkingsramme, samstundes som humoren og sjølvironien i forteljingane blir løfta fram. Minneberarane i Arkiv: De ufullendteer restar; det som er blitt igjen og som dei fleste finn verdilaust fordi det har ”utspilt sin rolle, eller aldri fikk den rollen det var tiltenkt”.14Å retta merksemda mot arbeidsmåtar og dygder som tidlegare stod høgt i kurs, men som i dag har tapt terreng, står alltid i fare for å hamna i nostalgien. Når Arkiv: De ufullendteunngår det, heng det saman med at desse plagga er uferdige og uperfekte, for ikkje å seia direkte mislukka. Det er eit påfallande trekk ved mykje av den samtidskunsten som baserer seg på funne materiale, at det ofte er det kasserte, som blir løfta fram. Ved å rette merksemda mot det som aldri blei ferdig eller enda som mindre vellukka, får Kari Steihaug fram ei side ved det å strikka som sjeldan er blitt fortalt. Vanlegvis skjuler vi uhell og fiaskoar, men når ho ønskjer at fleire skal få del i slike erfaringar er det fordiho veit at mange vil kjenna seg att i desse forteljingane. Plagga som Kari Steihaug samlar på og som ho brukar som kunstnarleg råmateriale, står utanfor det verdisystemet og den logikken som pregar kapitalistisk vareproduksjon. Dei er ikkje blitt til for å tena pengar, men representerer meiningsfullt arbeid eller tidsfordriv. Verdien deira er korkje knytt til førestellingar om perfeksjon, effektivitet eller marknadspris, men til at dei er unike og personlege. Antroplogen Igor Kopytoff har peika på at i komplekse samfunn som fløymer over av kommersielle tilbod, eksisterer det ein djup lengsel etter det eineståande og særlege.15Å produsera salsvarer og skapa noko eineståande, er for han ei motsetning. Ved å løfta fram handarbeidet som produksjonsform og samla døme på klede tiltenkt familie og venner, synleggjer Kari Steihaug andre krinslaup for utveksling av ting og tenester enn dei som fyller næringslivssidene i avisene. Hennar kunstnarlege produksjon kan såleis både i valet av materiale og tematisk innhald (samt i kraft av å vera kunst), seiast å representera ei motkraft til vareøkonomien og kommersialiseringa som pregar stadig fleire sider ved samfunnet og kulturen. Arkiv: De ufullendtehandlar om alternative praksisformer og tenkjemåtar, og prosjektet viser med det at strikking er mykje meir enn ein teknikk. Det er ein kulturell praksis med ei rik historie, der mykje enno ventar på å bli undersøkt og fortalt.Notar1. Maria Fabricius: Ruinbilleder. København: Tiderne Skifter 1999.2. Craig Owens: ”The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism”, Beyond Recognition. Representation, Power, and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press 1992, s. 53.3. Joanne Turney: The Culture of Knitting. Oxford: Berg 2009, s. 216. Sjå også Sabrina Geschwandtner (red): KnitKnit. Profiles + Projects from Knitting’s New Wave, New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang 2007, og Jessica Hemmings (red.): In the Loop. Knitting Now,Oxford: Berg 2010.4. Lise Skytte Jakobsen: Ophobninger. Moderne skulpturelle fænomener. København: Revens Sorte Bibliotek 2005, s. 11.5. Ibid., s. 13.6. Ibid., s. 18.7. Jean Baudrillard: ”The System of Collecting”. I: John Elsner og Roger Cardinal (red.): The Culture of Collecting. London: Reaktion Books 1994, s. 13.8. Susan Stuart: On longing. Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham/London: Duke University Press 1993, s. 162. 9. Mieke Bal: ”Telling Objects: A Narrative Perspective on Collecting”. I: John Elsner og Roger Cardinal (red.): The Cultureof Collecting. London: Reaktion Books 1994, s. 105. 10. Eilert Sundt: Om husfliden i Norge, Oslo: Gyldendal 1975 [1867/68], s. 239.11. Mary M Brooks: ”’The flow of action’: Knitting, making and thinking”. I: Jessica Hemmings (red.): In the Loop. Knitting Now.Oxford: Berg 2010, s. 35.12. Judy Attfield: Wild Things. The Material Culture of Everyday Life.Oxford: Berg 2000, s. 48, 256-61.13. Grant Mc Cracken: Culture and Consumption. Bloomington: Indiania University Press, 1988/1990, s. 68–69.14. Kari Steihaug: Arkiv: De ufullendte og tingenes bakside, sjølvpresentasjon, Kunsthøgskolen i Bergen 19. mars 2010.15. Igor Kopytoff: ”The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process”. I: Arjun Appadurai (red.): The Social Life of Things. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press 1986, s. 80.

A Collection of Remnants-A Series on Knitting Translation Francesca Nichols

A ruin –not made of stone, but knitting: Stacks of garments packed so tightly together that they form a wall. That was the sight that confronted visitors to Kari Steihaug’s solo exhibitionat the West Norway Museum of Decorative Art in 2007, an exhibition that introduced the museum’s theme for that year of knitting. Ruinwas the title she gave the installation, and the malleable wall looked as though it could fall apart at any moment. Whether it was meant to be a sculpture or a pile of rags, a construction or a ruin, a monument or an anti-monument, is difficult to say. It was as variable in its meanings, as the work was unstable in a purely physical sense. This is characteristic of ruins, and can explain why artists throughout the centuries have been drawn to this motif.1 Because the ruin is fragmented; it appears as both open and vulnerable. At the same time it expresses change; yesterday it was something else than what it is today, and thatprocess will continue indefinitely. The fact that nothing is permanent, but is constantly in transition, is typical of modern life. The German philosopher Walter Benjamin therefore pointed to the ruin as a ideal allegorical emblem, and as Craig Owens has pointed out, this is related to the fact that a characteristic feature of allegory is a desire to drag the past with one into the present.2Read as an allegory, the ruin motif encompasses a tension: There is both an impulse to collect and take care of things here, as well as an attraction to the forces that exist in fragmentation and imperfection. This perspective provides meaning in an encounter with Ruin. Over 800 hand-knitted garments make up the building blocks of this work. It is not known who knitted them. The artist has acquired the garments at flee markets, in a kind of rescue expedition. But at some point in time someone had devoted time and work in knitting these pieces of clothing; and someone had used them for practical or other purposes. Now their time has passed, in any case these garments no longer fulfil any function for their owner.By constructing a ruin out of this material, Kari Steihaug has created an allegorical narrative about a form of handicraft in transition. The sections that have fallen apart can be an indication that decay and disintegration threaten, and dark colour tones contribute to underscoring such a gloomy interpretation. But the use of colour also gives the ruin weight. It stretches out across the room and creates a clear boundary that can serve both as a hindrance and as protection. Unwound lengths of yarn lie like spider webs everywhere. They can just as well mark the beginning of something new as the end of something old. A culture in transition can refer to what has disappeared and been lost, or to that which lives on in new forms. When it comes to knitting, there are more and more who claim that it is in the process of a renewal.3In this sense Ruinpositions itself as an ambiguous work in a rangebetween the transitory and permanence, between that which has been and that which shall be, drudgery and desire, sorrow and joy. This is a theme that runs like a scarlet thread throughout Kari Steihaug’s artistic production.Accumulation

Quantity speaks its own language in Ruin. We do not see the individual garments because they are interwoven and stacked in piles. A collection of things like this, which is not organised according to their functional use, but merely accumulated, is widespread in today’s sculpture or installation art. Art historian Lise Skytte Jakobsen calls attention to the fact that what happens with the use of this organising principle is a de-contextualisation of the objects; “The objects become something else simply by being organised in this way. In other words, the accumulation threatens the objects’ innate identity and their stable significance.”4We also experience this type of sculptures differently than the classic, encapsulated sculpture. In part, it demands that we as viewers move about differently based on how large the installation is, and in part, it does not encourage touch in the form of pats and caresses. Instead, in an encounter with this type of accumulation, one uses one’s fingers (in one’s mind) to fidget with, extract, replace and add to it.5That art based on accumulation (or mass, which is another typical organising principle for art during the last century) could exist at all is related to the establishment of a new post-modern concept of art. Where classical art is built on an understanding of the work as unique and original, created as it is by a ‘genius’ artist, accumulation often implies a direct or indirect criticism of a such an “aura-based” concept of art. The material that the accumulation is formed out of is often producedby different persons or enterprises. The artist’s role is to collect, file, arrange and present them in new ways. What is particular about Ruinis that the building blocks are not made of manufactured, mass produced things, or copies, but quantities of hand-made knitwear which bears within it its own popular culture story. Lise Skytte Jakobsen connects the accumulation principle with themes such as collection, memory and history.6 Three subjects that are descriptive of Kari Steihaug’s art, and all of which are combined in the present project Archive: The Unfinished Ones. As opposed to Ruin, accumulation is not used as an organising principle. This work is rather marked by another modern organising principle; the series. The material is knitwear that the artist has collected. More specifically it has to do with initiated garments that individuals (read: women) have had lying around and for various reasons never managed to finish. It is both entertaining and thought provoking to read the reasons for their having given up. For the knitwear is presented together with a short text based on the originator’s explanations, but written down and edited by the artist. In the choice of material and method, Archiv: The Unfinished Ones,insists on authenticity: These arereal objects from real life. The strategy can be compared to the scientific approach museums use when they decide upon the provenance and history of an artefact. And this form of artistic realism thus also becomes a catalyst for the work of recollecting on the part of those involved. But this realism is merely one aspect of this complex work. When one thing is described in detail, in a strange way it also becomes less familiar. When it is no longer taken for granted, it gains an aura of being something mysterious. From representing something trivial, the knitwear –because of the way that the artist chooses, collects, classifies and organises them into a system –becomes downright unusual.Collection For more than ten years Kari Steihaug has collected unfinished or aborted garments. The source material she has helped herself to is far greater in magnitude than has so far been converted into an artistic form in Archive:The Unfinished Ones. At the Annual National Exhibition of the Visual Arts (the Autumn Exhibition) in 2009 she exhibited seventy selected samples. Each of them were photographed separately, but presented in the same size and in identical frames, shoulder to shoulder in four rows. In this way she created a new system of documentation and presentation of the collection. As an artist she approaches to the role of collector both in the way that she organises her material, and in her interest in versions and variations. Yet in Archive: The Unfinished Onesthe rows of samples are not complete. In the last row she has left two places empty, as an indication that additional material will be added. The story of the unfinished garments is apparently not finished. As the philosopher Jean Baudrillard once said, it is this that guarantees the life of the series. To complete a series is to die, while the fact that it lacks something guarantees life.7It is a well-known claim that collections say more about the collector than about who it was that made the things. When an object, or a fragment of a garment in this case, is taken out of its natural context it no longer functions as a link between the originator and his or her surroundings. Defined by the framework that the collection comprises, they point instead back to the collector.8In Archive: The Unfinished Onesthe knitted fragments can be considered as words in the artist’s vocabulary, and then it makes no difference that she did not knit them herself. As with most collections, this one serves several aims as well: enlightenment and education are among the most obvious,9 but at the same time Archive: The Unfinished Onesbears witness to the artist’s mooring in a textile tradition. Knitting as handiwork and knitting as an artistic concept are not opposites here but are rather united in one and the same work. The collection as a collection is nevertheless merely a secondary theme of this complex work. What is more pressing are the questions that have to do with the material itself: the knitted garment. What does it mean to knit? Why knit? Who knits?KnittingPopular knitting or household knitting is the term given by culture historians to the knitted garments of ordinary people. It is this type of product that Kari Steihaug has collected. It is unclear when knitting became widespread in Norway, but from the 18thcentury on we know that knitting was one of the handicrafts taught to girls in schools for the poor, and during the 19thcentury, knitting had become common for women in all levels of society. As the Norwegian sociologist Eilert Sundt wrote in 1865:“There is no female activity, or type of home craft, that is as universalfor the entire gender.”10Since then knitting has been considered a typical female pastime, a low cultural, marginalised, amateur activity totally lacking in status as an artistic medium until the feminist artists of the 1970s began to challenge the hierarchy that dominated the choices related to material and medium. At the exhibition Kvinnfolk(Women) in Stockholm in 1975, Slithögen(Mountain of Toil) was one of the most memorable monuments: A gigantic mound composed of knitted socks and other garments that demanded mending and patching, marked as they were by wear and tear. Whether or not she can knit, the viewer knows that it has taken time to knit and mend all of these socks, justas it has taken time to wear them out. The mound served as a reminder of where the creative abilities of women have traditionally been channelled. Other artists, from Sheila Hicks to Christian Boltanski, began to use garments as metaphors for the human corpus. By this means they contributed to opening up to a post-modern mentality that is dominant today, which is that all types of materials can be relevant in the context of art. It is on the shoulders of these pioneers that Kari Steihaug stands when she now collects the unfinished knitting projects of women and brings to light the stories that lie behind them.As a technique, the fundamental principle of knitting is simple and almost anyone can learn how to cast stitches. However, there are few who are able to figure out how a sweater is made, what type of yarn was used, how the pattern is constructed or what type of technical problems (related to knitting) have been solved along the way. Even though Archive: The Unfinished Ones does not go into detail about this, several of the stories are related to such questions. The myth that knitting is easy is punctured, and this is an aspect of Archive: The Unfinished Onesthat makes the project interesting, also for cultural scholars. As knitting experts have pointed out, how one learns to knit or the pleasure involved in knitting is not very well documented.11 The selected examples show how diversified the knitting culture is, as well as how many different reasons there are for knitting. For most people knitting is a hobby, something one does for the sake of the pleasure and relaxation it affords. At the same time there is an aspect of usefulness to it. A new scarf, mittens or sweater, often intended for another person, is the aim. Knitting is something one does for others and not only for oneself. Many learn how to knit while they are pregnant, in order to make clothes for the future child. Or the garment is meant to be a gift for a lover, spouse or child. Many hopes and dreams are thus embedded in the knitwear, and this often explains why the garment was never finished: The love ended before the garment was finished, or the child grew faster than the knitted garment. Sometimes it was sorrow or anger that destroyed the desire and pleasure that had been the motivation behind the work. Although it never ended up as a finished product, the time that went into it and the emotions that were invested in it contribute to giving the work value. Even though changing fashions play a role, the women were personally involved in the choice of yarn and pattern. The combination of time, consideration and love, in so many words all of the good intentions, have made it downright difficult to get rid of these remnants. Instead they have been stored away, until Kari Steihaug got a hold of them and gave them new life as art.Carriers of Memory The knitted fragments in Archive: The Unfinished Onesdemonstrate what design historian Judy Attfield has pointed to as characteristic of material culture: they represent something tangible and something intangible at one and the same time; something physical and material as well as something social and emotional.12That they have not been discarded is the clearest proof that they encompass something important. Interestingly enough, many of the contributors express great relief that Kari Steihaug can use their knitted garments. It sounds almost as if a burden has been lifted from their shoulders, and that by her action, she has freed them of the tether that the objects represented.Being transferred from the private home sphere to a public art context represents the beginning of a new chapter in the biography of these knitted garments. They have a life of their own to a greater degree than before, and the memories that they carry can be recognised and valued by others. We interpret the garments as expressions of the persons’ who have made or used them, and of the culture they originated in, yet garments communicate in a more implicit and less open way than verbal language. As the anthropologist Grant McCracken reminds us, the extent of what the garments can communicate is very limited, as is the rhetorical effect with which they do it.13 This applies to an even greater extent to the clothing that exists only as a fragment. The strength of Archiv: TheUnfinished Ones–in the sense of the ability to communicate meaning –is therefore related to their quantity and their organisation into a series, which again creates a context and a framework for interpretation, at the same time that humour and self-irony in the stories are highlighted. The carriers of meaning in Archive: The Unfinished Onesare remnants; that which is leftover and which most people find worthless because it has “played out its role, or never received the role it was intended to have”.14To direct attention to working methods and virtues that have previously been important, but have lost ground today, is always in danger of ending up as nostalgia. When Archive: The Unfinished Onesmanages to avoid this, it has to do with the fact that these garments are unfinished and imperfect, not to mention outright failed. A prominent feature in much of contemporary art is that it is often based on found material, that is, it is often what has been discarded that is focused upon. By directing attention to what was never completed, or even something that was botched, Kari Steihaug manages to point to an aspect of knitting that has rarely been told. We normally hide our accidents and fiascos, but when she wishes to allow others to participate in such experiences, it is because she knows that many will be able to identify with these stories.The garments that Kari Steihaug collects and that she uses as her artistic raw material exist outside the value system and the logic that characterises the capitalist manufacturing of wares. They have not come into being in order to generate money, but represent meaningful work or pastimes. Their value is not tied to conceptions of perfection, effectiveness or market prices, but to the fact that they are unique and personal. The anthropologist Igor Kopytoff has pointed out that in complex societies that are overflowing with commercial offers, there is an intense longing for something unique and special.15 To produce wares for sale and create something unique are incompatible to him. By shedding light on a handicraft as a form of production, and collecting examples of garments intended for families and friends, Kari Steihaug illustrates alternative circuits for the exchange of goods and services than those that fill thecommercial ads in newspapers. Her artistic production –in both the choice of material and the thematic content (as well as by virtue of being art), can thus be said to represent a counter force to a market economy and the commercialism that affect more and more sides of our society and culture. Archive: The Unfinished Onesis about alternative forms of practice and ways of thinking, and the project thereby reveals that knitting is far more than a skill. It is a cultural practice with a rich history, wherethere are still many stories that have yet to be examined and told. Footnotes1. Maria Fabricius: Ruinbilleder. Copenhagen: Tiderne Skifter 1999.2. Craig Owens: “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism”, Beyond Recognition. Representation, Power, and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press 1992, p. 53.3. Joanne Turney: The Culture of Knitting. Oxford: Berg 2009, p. 216. See also Sabrina Geschwandtner (ed.): KnitKnit. Profiles + Projects from Knitting’s New Wave, New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang 2007, and Jessica Hemmings (ed.): In the Loop. Knitting Now,Oxford: Berg 2010.4. Lise Skytte Jakobsen: Ophobninger. Moderne skulpturelle fænomener. Copenhagen: Revens Sorte Bibliotek 2005, p. 11.5. Ibid., p. 13.6. Ibid., p. 18.7. Jean Baudrillard: “The System of Collecting”. In: John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (eds.): The Culture of Collecting. London: Reaktion Books 1994, p. 13.8. Susan Stuart: On longing. Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection.Durham/London: Duke University Press 1993, p. 162. 9. Mieke Bal: “Telling Objects: A Narrative Perspective on Collecting”. In: John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (eds.): The Culture of Collecting. London: Reaktion Books 1994, p. 105. 10. Eilert Sundt: Om husfliden i Norge, Oslo: Gyldendal 1975 [1867/68], p. 239.11. Mary M Brooks: “‘The flow of action’: Knitting, making and thinking”. In: Jessica Hemmings (ed.): In the Loop. Knitting Now.Oxford: Berg 2010, p. 35.12. Judy Attfield: Wild Things. The MaterialCulture of Everyday Life.Oxford: Berg 2000, pp. 48, 256-61.13. Grant Mc Cracken: Culture and Consumption. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988/1990, pp. 68–69.14. Kari Steihaug: Arkiv: De ufullendte og tingenes bakside(Archive: The Unfinished Ones and the reverse side of things), Self presentation, The Bergen National Academy of the Arts 19. March 2010.15. Igor Kopytoff: “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process”. In: Arjun Appadurai (ed.): The Social Life of Things. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1986, p. 80.